According to the World Database on Protected Areas, there are currently over 28,000 designated sites covering approximately 8% of the ocean’s surface.

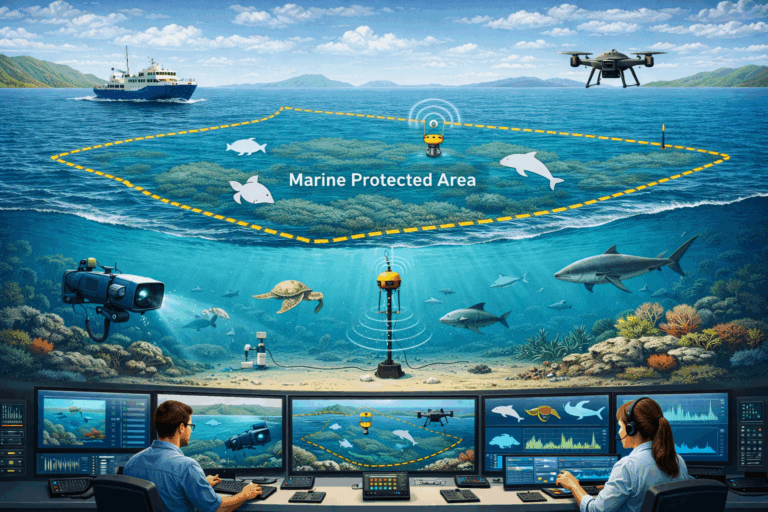

Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) have proliferated globally on a large scale. According to the World Database on Protected Areas, there are currently over 28,000 designated sites covering approximately 8% of the ocean’s surface. However, establishing protected zones or a national marine reserve is merely the first step; demonstrating effective conservation efficacy requires robust monitoring data and an effective system. Traditional survey methodologies such as dive transects or underwater visual censuses face inherent limitations. Specifically, visibility constraints, logistical costs, and the inability to observe cryptic, nocturnal, or deep-water species restrict comprehensive biodiversity assessment.

Passive Acoustic Monitoring (PAM) has therefore emerged as a transformative approach, enabling continuous, non-invasive observation suited for elusive marine species and challenging marine environment conditions. This analysis examines how passive acoustic systems are reshaping biodiversity monitoring within MPAs and how ocean data analytics supports marine conservation objectives.

Why monitoring biodiversity in marine protected areas is so challenging

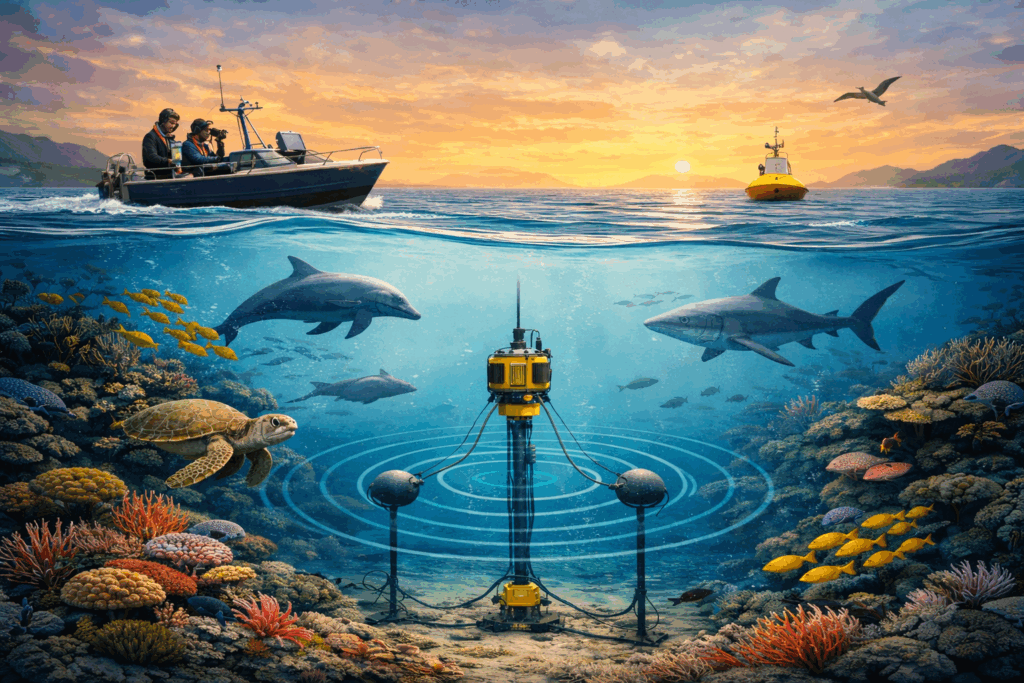

MPAs, any national marine reserve, and protected areas fulfill critical conservation functions by protecting key habitats such as coral reefs, coral gardens, coastal seagrass meadows, and coastal spawning grounds. These marine ecosystems support iconic mammals including marine mammals and sea turtles as well as threatened or endemic species requiring specific protection.

Effective management of these areas is a complex undertaking. It requires verification that marine protection measures are achieving intended conservation outcomes. Are marine species populations recovering? Is coral habitat quality improving over time? Are anthropogenic pressures being sufficiently mitigated to protect biodiversity? Answering these questions necessitates reliable, reproducible monitoring networks capable of quantifying biodiversity status and trends in the ocean and sea.

Limitations of traditional visual survey methods

Traditional visual census methodologies face multiple constraints that limit their overall effective utility. Underwater visibility fluctuates significantly based on depth, turbidity, and meteorological conditions, restricting ocean observation to narrow, favorable windows of time. Furthermore, numerous marine species exhibit cryptic behavior, concealing themselves within coral reef crevices or the substrate. Nocturnal ones remain virtually undetectable during diurnal surveys. Meanwhile, mobile fishes particularly cetaceans and pelagic transit through MPAs unpredictably, thereby evading scheduled census efforts in the marine environment.

Moreover, deep-water species inhabiting protected zones beyond recreational diving limits require Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs). Taken collectively, these factors yield an incomplete picture of biodiversity, potentially omitting significant components of protected ecosystems in the ocean.

Logistical and financial barriers

Logistical and financial constraints further exacerbate these observational limitations in a national reserve. Operating marine research vessels in the open ocean and sea costs thousands of dollars per day. Qualified scientific divers require substantial support, including safety equipment and adequate weather windows over time. Consequently, periodic campaigns provide temporal snapshots rather than continuous marine monitoring, potentially missing seasonal variations in marine biodiversity presence.

Furthermore, budgetary restrictions impose prioritization, often resulting in monitoring programs focused on charismatic species at the expense of broader community assessments in the MPA system. The challenge for MPA, national marine reserve, and protected area managers lies in securing comprehensive, effective, global marine data to support evidence-based marine conservation decisions and coastal development.

Passive acoustic systems: Listening to biodiversity instead of just observing it

Passive Acoustic Monitoring (PAM) distinguishes itself through effective technology application. It utilizes hydrophones, underwater microphones that record ambient ocean sounds without emitting signals.

Unlike active sonar, which emits pulses capable of disturbing marine life, PAM systems passively listen to natural soundscapes and biological vocalizations in the sea. Autonomous recorders deployed on the ocean seafloor or ocean platforms collect continuous data over weeks or even months of time. Concurrently, cabled observatory networks and systems enable real-time data transmission, facilitating reactive monitoring and adaptive MPA management.

The acoustic signatures of marine life

Marine organisms produce diverse acoustic signatures that enable species detection and behavioral assessment. Cetaceans generate clicks for echolocation, whistles for communication, and complex songs for reproduction. Many fishing and non-fishing species produce sounds via swim bladder vibration, jaw grinding, or fin movements during territorial displays.

Similarly, invertebrates create characteristic crackling sounds that dominate specific coral habitats. These biological sounds blend with physical processes and human activities noise to form complex acoustic environments. These sea “soundscapes” serve as a defining metric for marine ecosystem health and marine biodiversity.

Key advantages for MPA monitoring

Several distinct advantages position PAM as a critical asset for MPA monitoring networks. First, its non-invasive methodology avoids disturbing sensitive species or habitats. This is particularly vital in protected zones and protected areas where minimizing human activities and marine activities is paramount for marine protection.

Second, continuous operation enables 24/7 surveillance, capturing nocturnal species, seasonal patterns, and episodic events. Furthermore, its weather-independent nature allows for data collection during sea storms when vessel-based fishing activities are suspended.

Finally, long-term deployments spanning months or years of time reveal temporal dynamics, population trends, and phenological shifts in response to protection measures—phenomena often invisible to spot surveys in an established MPA.

Case of the great barrier reef marine park, Australia

The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park, the world’s largest marine protected area and largest coral system, benchmarked protected zones against fishing grounds. Marine data revealed that fully protected zones in this established marine reserve exhibited a 78% higher fish chorus intensity compared to partially protected areas. This global example of a largest national marine reserve proves that effective protection can protect marine species.

From soundscapes to indicators: How passive acoustics supports biodiversity assessment

Workflows commence with Quality Control protocols. Subsequently, spectral analysis visualizes ocean sound frequencies over time using spectrograms. Automated detection algorithms identify target sounds, including species-specific vocalizations or human activities noise. Machine Learning classifiers, trained on reference libraries, distinguish species based on acoustic features, enabling the automated processing of thousands of recording hours in the MPA.

Leveraging acoustic indices as biodiversity indicators

Acoustic indices quantify soundscape properties correlating with biodiversity.

The Acoustic Complexity Index measures the heterogeneity of sound patterns, with higher complexity suggesting greater species diversity in protected areas.

The Acoustic Entropy Index evaluates community composition. The Bioacoustic Index focuses on biological sound energy, effectively filtering out physical and human activities components in the sea.

Species-specific population monitoring

Targeted species detection supports population monitoring. Automated detectors identify the presence of cetaceans, pinnipeds, and soniferous fishing species. For select species, call rates correlate with abundance, allowing for the estimation of trends. Seasonal detection patterns reveal habitat utilization. For protected species, acoustic detection documents MPA utilization, thereby supporting conservation value assessments.

Detecting anthropogenic pressures: Noise and traffic inside marine protected areas

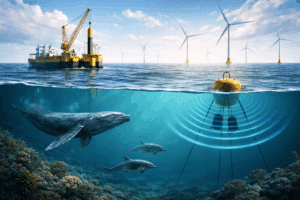

Even within protected boundaries, Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) remain subject to human activities, including maritime fishing traffic, industrial fishing activities, and coastal development.

The pervasive threat of underwater noise

Commercial shipping, recreational fishing boating, and coastal construction projects all generate noise with the potential to impact marine life. While MPAs and any national reserve strictly regulate extractive fishing activities, acoustic disturbance frequently receives less protection attention. This oversight persists despite well-documented biological impacts on marine species, ranging from behavioral disruption to physiological stress.

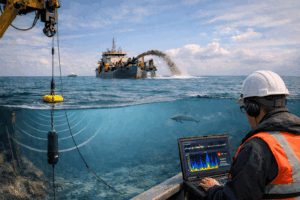

Quantifying noise exposure

Passive Acoustic Monitoring (PAM) systems quantify human activities noise exposure within MPAs. Sound Pressure Level measurements characterize ambient ocean environments. Spectral analysis identifies dominant noise sources such as propeller cavitation enabling attribution to specific marine activities. Meanwhile, temporal analysis reveals variations in noise exposure over time.

Integration with AIS vessel tracking data correlates acoustic detections with specific vessel identities, linking noise levels to sea traffic patterns and transit speeds.

Linking noise to biological impacts

Correlating human activities noise with biological activities provides critical insights for MPA management. Studies demonstrate altered calling behavior among marine mammals in high-noise areas. Fishing species spawning aggregations also exhibit sensitivity to acoustic disturbance.

By concurrently monitoring noise levels and biological soundscapes, managers can assess whether human activities or marine activities are undermining the MPA system conservation objectives. This integrated assessment supports adaptive management strategies designed to protect critical biological windows and protect marine species from human activities.

A tool for enforcement

Acoustic monitoring supports regulatory enforcement by detecting illegal fishing activities. Unauthorized fishing vessel incursions into protected zones and around marine islands generate acoustic signatures. Illegal fishing operations, including dynamite fishing, produce distinctive sounds. While acoustic monitoring does not replace physical interdiction, it provides a supplementary surveillance capability in a vast national marine reserve.

Sinay’s contribution: Bridging science, technology, and conservation

Sinay combines marine data, underwater noise monitoring, and advanced analytics to empower Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) in assessing both biodiversity and anthropogenic pressures.

Our approach integrates acoustic monitoring within broader environmental intelligence frameworks. We recognize that effective MPA management necessitates a deep understanding of the interplay between biological communities, the marine environment, and human activities. By synthesizing diverse ocean data streams, we facilitate comprehensive ecosystem assessments that support evidence-based marine conservation decisions and the established MPA system.

Integrated platform capabilities

Our platform features are specifically engineered to support marine acoustic monitoring. We integrate acoustic recordings from autonomous hydrophones and cabled observatory networks into centralized data management systems. Automated processing pipelines apply detection algorithms to convert raw recordings into structured biodiversity metrics.

Visualization tools subsequently render soundscapes, marine species detections, and sea noise level maps via intuitive interfaces to help protect marine species.

Enriching analysis with complementary data

Cross-referencing ocean data with complementary information sources significantly augments analytical capability. We correlate biological sound patterns with ocean conditions to reveal the environmental drivers determining marine species distribution.

Integration with AIS vessel tracking enables the precise quantification of noise exposure in protected zones. Furthermore, we utilize habitat maps to overlay acoustic monitoring locations in the MPA. This multidimensional approach helps protect biodiversity and protect marine life.

We collaborated with a Mediterranean MPA conducting a comprehensive biodiversity assessment. Our integrated platform enabled managers to visualize seasonal cetacean presence, correlate detections with marine species abundance, and quantify maritime fishing traffic during sensitive periods of time.

This synthesis subsequently justified the implementation of seasonal restrictions on recreational fishing boating to protect marine species. These measures successfully reduced acoustic disturbances in the protected area while maintaining public access to the sea.

Delivering actionable conservation outcomes

The value provided to MPAs, national reserve institutions, and marine conservation organizations extends beyond data processing to offer operational support for marine protection.

We provide tools that make marine data actionable, translating complex soundscape information into clear indicators that support MPA management decisions. Automated reporting capabilities generate periodic assessments, documenting protection efficacy and supporting regulatory compliance in an established national marine reserve. Additionally, our collaborative project frameworks facilitate global networks where expertise in marine conservation converges to protect biodiversity.

Conclusion

Passive Acoustic Monitoring unlocks unprecedented capabilities for biodiversity assessment within Marine Protected Areas. It facilitates the observation of ecosystems often obscured from traditional methods in the ocean. Continuous, non-invasive monitoring captures marine species and behaviors inaccessible via visual surveys while simultaneously quantifying the human activities and marine activities affecting marine conservation objectives.

By combining rigorous scientific methodologies with advanced analytics platforms, MPA system managers can effectively measure protection efficacy, detect emerging threats, and demonstrate conservation success in a national reserve. We remain committed to advancing marine acoustic monitoring through an established global system that transforms underwater sea sound into tangible marine protection and help protect the largest marine protected areas. We must protect coral reefs, protect fishing grounds, and protect our global ocean biodiversity for the future development of the marine environment.

FAQ

Passive Acoustic Monitoring (PAM) is a non-intrusive technique that uses underwater microphones (hydrophones) to record sounds produced by marine species and human activities. In Marine Protected Areas, PAM is used to monitor biodiversity by detecting vocal species such as marine mammals, fish, and invertebrates, while also tracking anthropogenic noise from vessels or offshore activities. This approach enables continuous, long-term observation without disturbing ecosystems.

PAM is particularly effective in MPAs because it operates 24/7, in all weather and light conditions, and over large spatial scales. Many marine species are difficult to observe visually but produce distinctive sounds, making acoustic data a reliable proxy for presence, behavior, and seasonal patterns. PAM also helps assess habitat quality and human pressure, supporting evidence-based conservation and management decisions.

Passive acoustic systems provide objective, long-term datasets that help managers evaluate the effectiveness of protection measures, detect changes in species distribution, and identify emerging threats such as increased vessel traffic or noise pollution. By integrating PAM data into environmental reporting and impact assessments, MPAs can improve regulatory compliance, adaptive management strategies, and the overall protection of marine biodiversity.

Maritime Applications