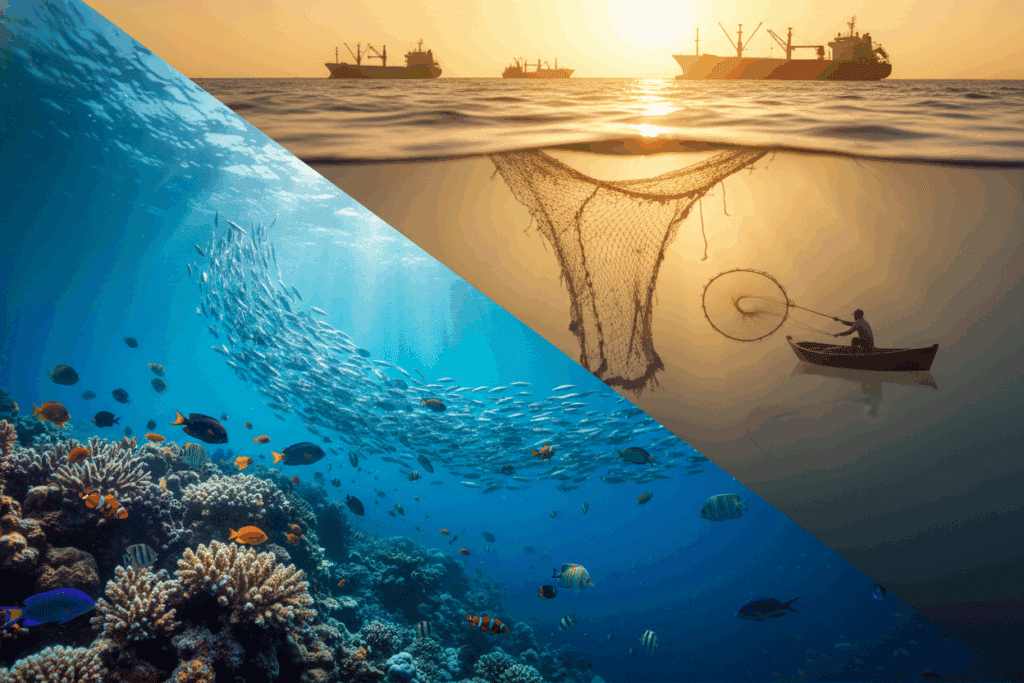

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), over 35% of global fish stocks are currently impacted by overfishing. The health of our ocean and its marine species is at stake.

The future of global fisheries and our food supply depend on sustainable practices. The sustainability of seafood is a major concern for every human community. At the same time, about 90% of world trade moves by sea, with more than 100,000 commercial vessels operating continuously across ocean basins. The health of these marine ecosystems is a priority for every community. The impact of overfishing threatens the entire food chain and the health of our oceans. The future of wild fish populations is a critical environmental issue that affects every human.

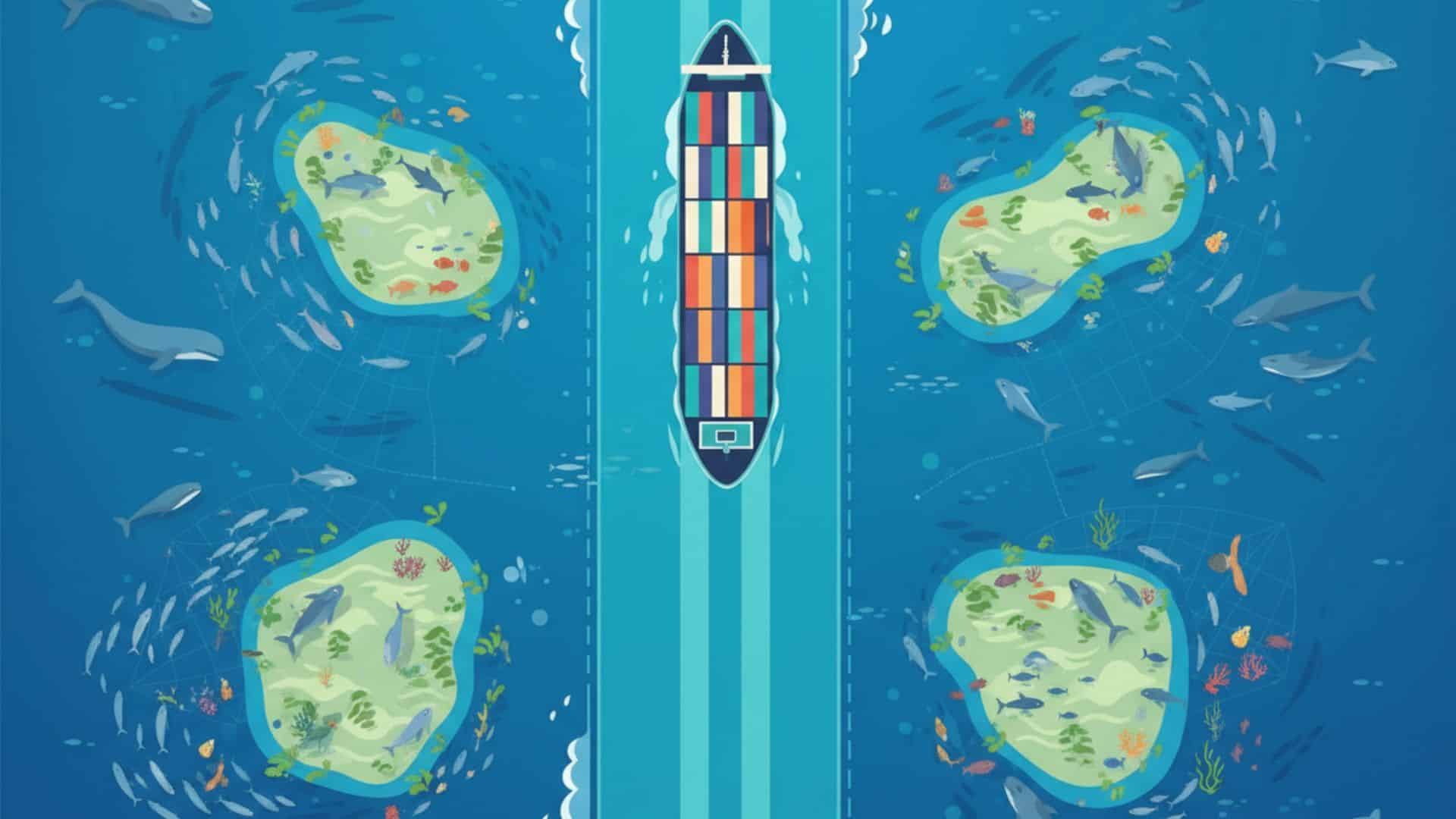

These two sectors, shipping and fishing, often share overlapping marine spaces, creating complex interactions that affect ecosystem health, biodiversity, and governance. The impact on fish populations and other marine species is significant. This requires data-driven fisheries management systems to address the impacts of overfishing.

When shipping and fishing overlap: understanding the interactions

Maritime space allocation increasingly generates conflicts between shipping lanes and productive fishing grounds. This has a direct economic impact on the fishing industry and coastal communities. The future of these fisheries is uncertain due to the impacts of overfishing.

Competition for marine space

Major trade routes frequently traverse continental shelves where nutrient upwelling sustains dense fishing activity, crucial for global food security and many human communities. The Mediterranean Sea exemplifies this overlap, with heavy vessel traffic crossing traditional fishing zones where fisheries target specific fish species. Similarly, the South China Sea faces comparable challenges, as intense commercial navigation and fishing converge within one of the planet’s richest marine ecosystems. These practices threaten the sustainability of fish stocks.

For example, the tuna fisheries are heavily affected by overfishing. The impact on seafood availability is a growing concern for these communities. The health of the ocean is directly linked to these fishing practices. Without a change, the future of these fisheries is bleak. Sustainable aquaculture is being explored as an alternative food source.

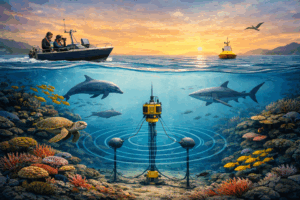

The hidden impact of underwater noise

Acoustic pollution from ships further complicates the picture for marine health. Propellers and engines emit low-frequency sounds that travel hundreds of kilometers underwater, a major environmental concern. Consequently, marine mammal species relying on echolocation experience masking effects. Research in Marine Policy reports behavioral disruptions such as altered migration routes and decreased foraging efficiency. This impact on marine species is a serious threat to the health of ocean ecosystems. The social and economic well-being of the human community is linked to this environmental health. The impacts on fish populations are also under study.

Direct threats: ship strikes and ghost nets

Physical interactions between ships and marine life also cause direct mortality. Ship strikes remain a leading cause of death for large whales. Fishing activities add to the toll through “ghost nets” — abandoned gear that continues trapping marine life. Other destructive fishing practices, such as bottom trawling, also have severe environmental impacts. Trawling can destroy sensitive habitats like coral reefs, and this method often results in high levels of bycatch, where many non-target species are caught and discarded. The long-term impact of trawling on fish stocks is a major concern. The bycatch problem in many fisheries is a major contributor to the decline of wild species. The Bay of Biscay illustrates this overlap vividly. This example shows the urgent need for change. In Australia, for example, programs are in place to retrieve ghost nets to protect marine species.

Invasive species from ballast water

Meanwhile, ballast water discharge adds another layer of complexity to the health of marine ecosystems. By transporting organisms across regions, ships inadvertently introduce invasive species that disrupt local ecosystems and fisheries. The impact on wild fish populations and the broader food web can be devastating. We must find a way to manage this for a sustainable future. The impact on aquaculture operations is also a major economic concern, affecting the global seafood supply.

The ecological toll: cumulative impacts on marine life

Overfishing fundamentally reshapes marine food webs by removing top predators and valuable commercial species. The impact of overfishing is a primary driver of declining ocean health. The sustainability of our seafood supply is at risk. The human community must address this environmental challenge.

Destabilizing ecosystems through pollution and depletion

The Mediterranean bluefin tuna — now reduced to just 15% of its historical abundance — exemplifies how excessive fishing destabilizes entire ecosystems. The future of this iconic species is in doubt due to these harmful practices. In parallel, both sectors contribute to chemical pollution. The health of the food chain is compromised. A sustainable future for our oceans depends on addressing both overfishing and pollution. The human community has a responsibility to drive this change. Sustainable aquaculture is often proposed as part of the solution to provide alternative food sources and reduce pressure on wild fish stocks.

The compounding effect of multiple stressors

However, the ecological consequences rarely occur in isolation. Synergistic effects emerge when multiple stressors interact. Noise-stressed fish, for example, feed less efficiently, compounding the direct depletion caused by overfishing. A Frontiers in Marine Science study found that recovery times for depleted stocks are longer in areas exposed to both habitat degradation and chronic noise. The North Sea’s Atlantic cod population illustrates this challenge. Despite strict catch limits, recovery has lagged. This example underscores the need for integrated management to address simultaneous stressors on fish stocks and marine health. The future of these fisheries is at stake. The economic impacts on the fishing community are severe.

Interrupting essential migration routes

Migration disruptions add another dimension. Many marine species rely on specific routes. Acoustic pollution can delay migrations, while ship strikes inflict direct losses, pushing already vulnerable fish populations toward critical thresholds. The future of many wild species depends on our ability to mitigate these human impacts. This requires a fundamental change in our approach to the ocean. This is a global environmental problem.

Governance and regulation: toward integrated ocean management

Global ocean governance remains fragmented. The IMO regulates shipping, while the FAO oversees fisheries. This separation leaves cumulative impacts falling between institutional responsibilities. This is a challenge for global sustainability. A sustainable future requires a unified approach.

The challenge of fragmented governance

Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) aim to address these gaps, yet coverage remains limited. This is not enough to secure the future health of fish stocks and marine ecosystems. These practices need to change. The sustainability of global fisheries is compromised. This has major social and economic impacts on communities that depend on fishing.

New treaties and regional initiatives

Recent progress brings cautious optimism for the future of global ocean governance. The 2023 UN Treaty on Marine Biodiversity introduces a framework for establishing MPAs and mandates environmental impact assessments. Regional initiatives also point the way forward. The European Union’s Maritime Spatial Planning Directive, for example, requires member countries to coordinate marine uses — from shipping and fishing to renewable energy and conservation. This is a positive change for sustainability. Australia, for example, is a leader in implementing such marine spatial planning to protect its coral reefs and fisheries.

From pioneering models to a new management philosophy

The Pelagos Sanctuary stands as a pioneering model. It safeguards cetaceans from fishing bycatch and ship strikes. The agreement promotes modifications to fishing gear — practical practices showing how cooperation can mitigate overlapping impacts. Ultimately, ecosystem-based management (EBM) provides the conceptual foundation for this shift. By considering entire ecosystems, EBM integrates biological, social, and economic data to sustain long-term ocean health. This is the key to sustainable fisheries and sustainable aquaculture.

Technology and data: tools to harmonize ocean uses

Comprehensive monitoring now forms the backbone of integrated ocean management. Satellite-based AIS tracking allows real-time mapping of vessel movements. Platforms such as Global Fishing Watch analyze AIS data to identify fishing patterns. When combined with biological datasets, these tools pinpoint hotspots requiring regulatory attention, a key step for sustainable fisheries. The health of fish stocks depends on this data. The future of fishing will be data-driven.

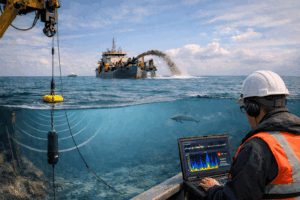

Sinay’s metocean monitoring solutions

We deliver integrated platforms that transform diverse datasets into actionable intelligence for ocean management.

Integrating data for ecological insight

Our metocean analytics merge environmental data with AIS tracking, enabling precise identification of zones where shipping routes intersect biodiversity-rich regions. This insight helps authorities design navigation corridors that minimize ecological disturbance to marine species. This is a key part of sustainable practices for the future. Our goal is to improve ocean health.

A focus on acoustic monitoring

Noise monitoring represents another cornerstone of our approach. By deploying hydrophone networks, we measure ambient noise. The system correlates exposure levels with sensitive species distributions, generating risk maps that inform policy decisions to protect marine health. The impact on fish populations is a key metric. This environmental monitoring is crucial.

A case study in the mediterranean

In the Mediterranean, a major port authority adopted our integrated monitoring system to address conflicts between rising vessel traffic and protected cetacean populations. The platform combined AIS data, passive acoustic sensors, and field observations. Based on these insights, authorities introduced seasonal speed limits. This is a great example of data-driven change.

Enabling adaptive management with real-time analytics

Real-time analytics also enable adaptive management. When aggregations of marine species are detected in shipping lanes, alerts can prompt temporary rerouting. Machine learning models reveal hidden correlations in large datasets, supporting proactive decision-making for a sustainable future for all human communities. The sustainability of global food systems is at stake.

Building a sustainable blue economy: a shared responsibility

A sustainable ocean economy demands coordination between sectors long managed in isolation. The blue economy vision promotes maritime activities that are both environmentally responsible and socially inclusive, for the benefit of all people. The future of our food supply depends on it. This vision is essential for the health of our oceans.

Education is also vital. The school system can play a key role in promoting ocean health. By integrating marine science and sustainability into the curriculum, a school can raise awareness about overfishing and climate change, empowering students to make informed choices about sustainable seafood. For example, many schools in Australia have programs connecting students with their local marine environment. Every school has a part to play.

The vision of a sustainable blue economy

Encouragingly, best practices already exist. Slow steaming lowers fuel use and underwater noise. Similarly, establishing buffer zones around sensitive habitats allows coexistence between industrial activity and ecological preservation, which is good for the health of all marine species and fish populations. This is a sustainable practice.

Fostering transparency and accountability

Transparency also plays a central role. Our digital platforms help operators monitor their environmental performance, fostering accountability. Through technology transfer and training initiatives, we ensure equitable access to advanced analytical tools, allowing emerging countries to participate fully in sustainable practices. The sustainability of global seafood is a shared goal. The future of fishing depends on this transparency.

A model of regional collaboration: the baltic sea

The Baltic Sea provides a successful regional example. Under the Helsinki Commission (HELCOM), nine countries coordinate efforts spanning shipping, fishing, and habitat conservation. Joint assessments evaluate ecosystem health holistically, while targeted actions — such as adjusting fishing quotas — demonstrate how collaborative governance can deliver measurable results for fish stocks.

Reconciling prosperity with preservation

Ultimately, the blue economy’s promise lies in reconciling prosperity with preservation. By combining innovation, regulation, and shared responsibility, humanity can shift from exploiting the ocean to stewarding it. Supported by data-driven technology and global cooperation, this transition can safeguard marine ecosystems while sustaining the livelihoods that depend on them. This is the future we must build for our oceans. The health of the global community is linked to the health of the ocean. This requires a fundamental change in human behavior.

FAQ

Both activities create cumulative stress on marine ecosystems. Overfishing reduces key species and disrupts food webs, while shipping contributes to noise pollution, habitat disturbance, and potential collisions with marine life. Together, they intensify biodiversity loss and ecosystem imbalance.

Overfishing removes species faster than they can reproduce, leading to declining fish populations and altering trophic interactions. This destabilizes entire ecosystems and reduces the resilience of oceans to other pressures like climate change and pollution.

Shipping introduces several stressors: underwater noise disrupting marine mammals, emissions contributing to climate change, ballast water spreading invasive species, and physical disturbances from vessel traffic. These impacts accumulate, especially in heavily trafficked regions.

Solutions include enforcing sustainable fishing quotas, adopting eco-friendly shipping technologies, creating marine protected areas, improving vessel routing to reduce noise, and implementing international regulations like IMO emission standards. Collaboration across sectors is key to long-term ocean health.

Maritime Applications