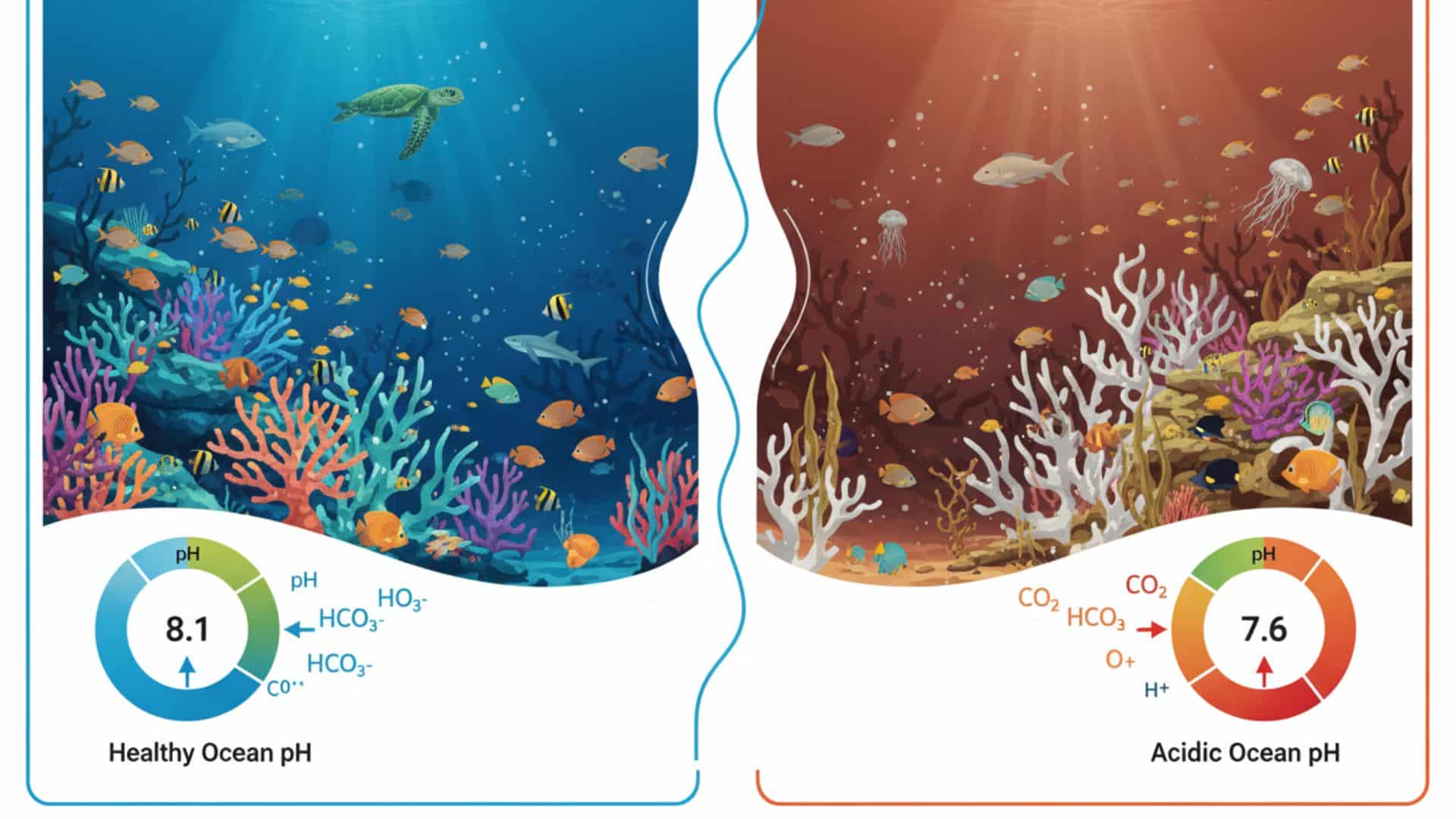

Ocean acidification remains one of the most underestimated consequences of anthropogenic carbon emissions. Global oceans have absorbed nearly 30% of carbon dioxide released since the Industrial Revolution, causing an increase in ocean acidity and fundamentally disrupting marine chemical equilibria.

This change affects marine life, fish, corals, and other species, with profound impacts on ecosystems, coral reefs, shells, and food cycles. Surface seawater carbonate and alkalinity levels are declining, altering ions and oxygen availability, while higher carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere drive pollution and long-term climate change.

Observations over many years, including NOAA data, confirm that acidic seawater will continue affecting marine organisms, life, and fisheries. This study highlights the scale of these effects, showing that human emissions and rising carbon dioxide will increase ocean acidity and impact coral, fish, and shell-bearing species. Understanding these changing chemical conditions is critical, and data-driven monitoring informs mitigation pathways and adaptive strategies. This will shape the future of the ocean, its reefs, and all life dependent on marine ecosystems.

The science behind ocean acidification

Ocean acidification results from a chemical process triggered by atmosphere carbon dioxide absorption. When carbon dioxide dissolves in seawater, it forms carbonic acid, which dissociates into hydrogen ions (H⁺) and bicarbonate ions (HCO₃⁻). The increased concentration of hydrogen ions lowers seawater pH, making the ocean more acidic. This chemical reaction, a core part of ocean acidification, reduces the availability of carbonate ions, which many marine organisms require to build calcium carbonate shells and skeletons.

The entire marine food cycle is affected by this process of ocean acidification. The human factor in these carbon emissions is undeniable. The health of countless organisms and marine species is at stake due to this carbon. The scale of this problem for our ocean is immense. Every species in the ocean will be affected by ocean acidification. The findings from NOAA on carbonate levels in seawater is a key part of this study on ocean acidification. The impact of carbon is clear.

The scale and source of chemical changes

Recent observations reveal the extent of ocean acidification. Average surface pH has dropped, reflecting a 30% increase in acidity. Moreover, the current rate of change is unprecedented, with cold regions experiencing stronger acidification due to higher carbon dioxide solubility at lower temperatures. This climate change will have profound effects on the sea. The reports from these regions is particularly concerning for marine organisms facing this acidification. The carbon absorption is higher in the cold ocean.

Importantly, the link to human activity is clear. Since 1750, over 400 billion tons of carbon have been released from human activities. The ocean absorbs a large part of these carbon emissions annually, moderating atmosphere warming but altering marine biogeochemical cycles, leading to ocean acidification.

NOAA’s Ocean Chemistry Program monitors these shifts using pH, pCO₂, total alkalinity, and dissolved inorganic carbon measurements from seawater. This NOAA study on seawater is vital for understanding ocean acidification. The levels of dissolved carbon are rising to high levels. The information collected by NOAA helps us understand the climate.

Global monitoring and data collection

Continuous monitoring is critical to understanding ocean acidification. Observatories, floats, and satellites collect high-resolution data across ocean basins. Integrating measurements with models allows projections of future ocean acidification under different carbon emissions scenarios.

UNESCO ensures standardized protocols, guaranteeing data quality across networks. The changing state of the sea is a key focus. This information is essential for scientists studying the ocean and its acidification. This data helps track carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere and seawater. The problem of ocean acidification requires this level of detailed carbon data.

For example, the Hawai’i Ocean Time-series has recorded a steady pH decline over many years, tracking rising atmosphere carbon dioxide concentrations. These long-term observations provide definitive evidence linking human-caused carbon emissions to ocean acidification and support climate models. This data is crucial for every study on the topic of climate change and ocean acidification.

Impacts on marine life and ecosystems

Ocean acidification disrupts calcification in many marine organisms. Reduced carbonate ion availability makes shell and skeleton formation energetically expensive for calcifying species, including corals, mollusks, and plankton. Laboratory studies demonstrate growth rate reductions in various species under future acidic scenarios caused by this ocean acidification.

Pteropods—planktonic snails at the base of many marine food webs—show shell dissolution in undersaturated water. These organisms are vital for marine life in the ocean. The survival of these organisms is threatened by this change. The impacts of ocean acidification are significant for every marine species. Every part of the ocean is affected by this carbon-driven acidification.

Threats to coral reefs and food webs

Coral reef ecosystems face compounded threats from ocean acidification and warming. While thermal stress causes coral bleaching, ocean acidification weakens skeletal structures. The Great Barrier Reef has experienced unprecedented bleaching, with ocean chemistry changes limiting recovery. A study published in Nature Climate Change projects that current carbon emission trajectories could eliminate 99% of coral reefs. The impacts on these marine ecosystems from ocean acidification are severe.

Food web disruptions cascade through marine ecosystems as foundational species respond differently to changing chemistry from carbon and acidification. Calcifying phytoplankton, vital for the oceanic carbon cycle, show variable responses. These shifts alter prey availability for higher trophic levels. Commercially important fish species experience behavioral changes under elevated carbon dioxide levels in the water. The Bering Sea shows acidification-related changes in king crab populations.

Socioeconomic consequences

Socioeconomic consequences extend beyond environmental concerns. Fisheries and aquaculture provide livelihoods for 200 million people. Ocean acidification threatens shellfish aquaculture, including oyster, mussel, and clam production. Pacific Northwest oyster hatcheries experienced massive larvae mortality attributed to acidified upwelling water. Coastal tourism dependent on coral reef ecosystems generates $36 billion annually—revenue threatened by reef degradation from ocean acidification.

Researchers monitoring Alaska’s Bering Sea documented shell dissolution in wild pteropods. These organisms, a critical food source for valuable species, showed damage consistent with laboratory experiments on ocean acidification. The finding demonstrated that theoretical impacts had manifested in natural populations, raising concerns about the future of marine life. The changing chemistry of the sea, driven by carbon, is a major factor in this ocean acidification.

Hidden consequences for the maritime industry

While ecological impacts dominate discussions, the maritime industry faces consequences from changing ocean chemistry and ocean acidification. Accelerated corrosion is a significant concern. Lower pH increases corrosion rates in steel hulls. A study by classification societies indicates that ocean acidification could increase maintenance costs if systems aren’t adapted to changing seawater conditions. The surface of these shells is directly affected, as is the surface of metal structures. This carbon-related problem impacts the entire ocean.

Operational challenges to vessel systems and infrastructure

Acidified seawater poses operational challenges for ballast water systems. In parallel, heat exchangers may face accelerated corrosion, reducing efficiency and asset lifespan. The fleet is at risk from the acidification of the ocean.

Infrastructure durability must account for ocean chemistry projections. Ports may underestimate long-term corrosion, with steel degradation accelerated under higher dissolved carbon dioxide levels in the water. A Singapore study projected that maintenance intervals could shorten. This increase in maintenance is a direct result of climate change and the ocean’s absorption of carbon. This will have implications for every ocean.

The need for data-driven maintenance

Predictive maintenance must integrate ocean chemistry parameters to combat ocean acidification’s effects. By correlating pH variations and other factors with corrosion rates, operators can optimize schedules. We have developed capabilities linking monitoring with asset management frameworks, enabling data-driven strategies that account for changing ocean conditions and seawater properties. The surface of materials is particularly exposed to these changes. This data-based approach will become standard for the ocean.

Monitoring and data: the key to understanding ocean chemistry

Comprehensive ocean chemistry monitoring requires high-frequency measurement of multiple parameters to track ocean acidification. Beyond pH, critical variables include partial pressure of carbon dioxide (pCO₂), total alkalinity, dissolved inorganic carbon, carbonate saturation states, and temperature. These parameters interact through complex chemical equilibria in seawater. Modern autonomous sensors enable continuous, long-term monitoring of the ocean. This data is essential for all marine scientists studying carbon and acidification. This study is ongoing.

Technological advances revolutionize ocean observation. Profiling floats with pH sensors now operate within the international Argo network, providing subsurface data on ocean acidification. Moored buoys deliver real-time data supporting operational oceanography and climate research. Miniaturized sensors expand observation networks at modest cost. Data telemetry via satellite makes observations available within hours. This network of data will improve our understanding of the ocean and its carbon cycle.

Sinay's metocean analytics solutions

Sinay provides comprehensive ocean monitoring capabilities. Our platform integrates data from multiple sources—sensors, vessels, satellites, and models—creating unified views of ocean conditions. Real-time data assimilation improves model accuracy, enabling reliable forecasts. The correlation between physical and biogeochemical processes allows prediction of ocean acidification hotspots. These data help us understand the changing sea and the spread of ocean acidification. Our data platform will be a key tool against carbon.

Our analytics tools enable operators to access ocean chemistry data. Route planning applications can incorporate pH forecasts. Port authorities gain visibility into local ocean chemistry trends, informing infrastructure maintenance. The integration of diverse data streams creates comprehensive situational awareness of the entire marine environment and the state of ocean acidification.

A European offshore wind operator deployed our ocean monitoring solution. Continuous pH monitoring revealed significant variability in ocean chemistry, a sign of ongoing ocean acidification. This data informed the selection of corrosion-resistant materials for subsea cables. Additionally, environmental baseline data supported regulatory compliance and communication regarding construction impacts on marine ecosystems. The chemical state of the water was a key factor. This kind of data on carbon and acidification will be crucial for all offshore projects in the ocean.

Mitigation and adaptation: a shared responsibility

Addressing ocean acidification requires simultaneous emissions reduction and ecosystem protection. Maritime decarbonization mitigates ocean acidification by limiting future carbon dioxide absorption. Alternative fuels eliminate carbon emissions. Operational efficiency improvements reduce fuel consumption and corresponding carbon emissions. The industry’s transition toward net-zero represents a critical contribution to fighting ocean acidification. This effort will require a commitment to address climate change and reduce carbon.

Ecosystem restoration as a complementary solution

Ecosystem restoration provides complementary benefits. Coastal blue carbon ecosystems—mangroves, seagrass beds—absorb carbon dioxide through photosynthesis while providing habitat for commercial fish species. These habitats also locally moderate pH, creating refugia where calcifying organisms may persist despite broader ocean acidification trends. Restoration initiatives delivering multiple benefits merit increased investment. The health of these organisms and marine species depends on reducing carbon in the ocean.

International coordination and industry contribution

Efforts like the Global Ocean Acidification Observing Network (GOA-ON) set standards for monitoring, data sharing, and research, with institutions in 90 countries contributing observations. Maritime industry participation enhances these networks, providing operational data and adopting best practices. The climate crisis demands this level of cooperation to solve the ocean acidification problem.

FAQ

Ocean acidification occurs when the ocean absorbs excess atmospheric CO₂, forming carbonic acid and lowering seawater pH. This shift in chemistry reduces carbonate ion availability, which many marine organisms need to build shells and skeletons.

Acidification weakens calcifying organisms such as corals, mollusks, and some plankton, making them more vulnerable to predation and environmental stress. These changes ripple through food webs, affecting fish populations and overall ecosystem stability.

Lower pH levels can accelerate the corrosion of ship hulls, engines, and port infrastructure. Acidified waters may also influence navigational safety by altering species distribution, increasing biofouling pressure, and affecting ecosystem-based maritime regulations.

Solutions involve reducing global CO₂ emissions, improving vessel efficiency, adopting low-carbon fuels, and implementing monitoring programs to detect pH changes. Protecting vulnerable ecosystems and strengthening environmental policies also play a crucial role.

Maritime Applications